I’m just returning from a wonderful and sporty, private Advanced Coastal Cruising class aboard a beautiful brand-new Dufour 530. This weekend brought gale-force winds and a wonderful opportunity to see what the boat and crew could do. This class is the fifth in American Sailing Association’s instructional series and covers what a sailor needs to know to make coastal passages in exposed waters where retreat to the protection of shelter is often not possible when the weather deteriorates. The forecast called for winds from the south exceeding 20 knots in the San Juan Islands into the Canadian waters north over a 72-hour period. The forecast on the Pacific Ocean and the adjoining water of the Strait of Juan De Fuca was the same but combined with seas exceeding 10 feet. When the owner reached out originally he told me that he was planning on sailing the boat to Mexico where he and his partner planned to winter aboard. He went on to say that he and his crew wanted to get some ocean experience and to learn about heavy-weather sailing. After looking at the forecast together we decided to head West to the ocean instead of north to the Strait of Georgia. This decision was based on the reluctance to have to sail back south at the end of the weekend into the 20-plus knot winds and choppy seas that wind over current produces. Instead, our decision to head west allowed us to head out into the ocean and strong winds on a more forgiving point of sail while leaving the option to quickly return to the lee and protection of Cape Flattery.

(The concept of apparent wind is an important subject in the material. In short, it is a fact that sailing into the wind adds the speed of the boat to the “true wind” speed. So, for example, a 50-foot boat sailing 8 knots into 30 knots produced the effect of 38 knots on the sails. This paired with the fact that wind-force grows exponentially while adding to the discomfort of sailing into the waves that are created by the wind makes the decision to pick a heading where the wind is on the side of the boat or “beam” and easy one. )

Whats wrong with this picture?

Prepared!

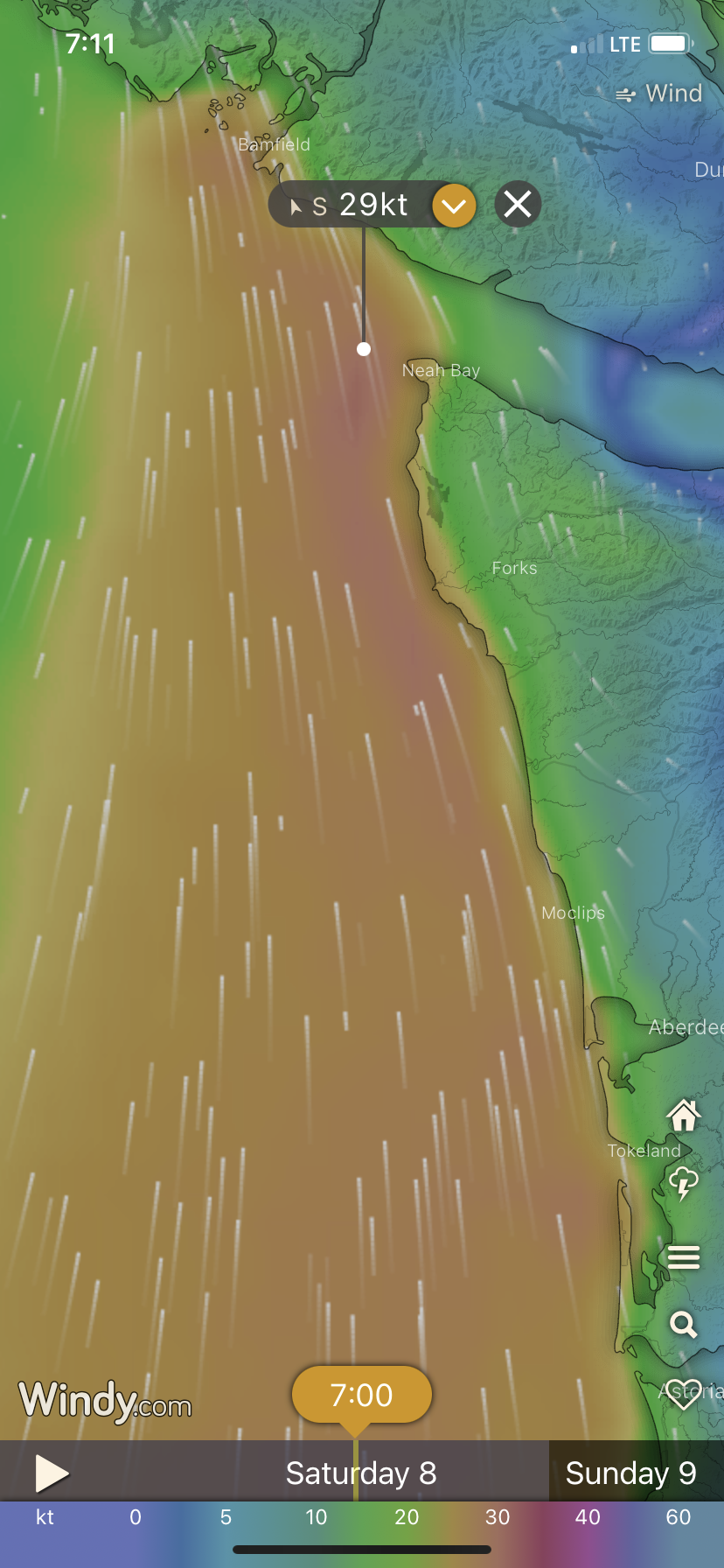

Our departure from Friday Harbor where the crew picked me up was slowed slightly by the strong flood at Cattle Pass and our entrance into the waters on the East end of the Straits of Juan De Fuca. Once in the Straits, there was enough wind from the Southwest to shake out the crisp folds of the French boat’s band new sails and to begin to find the optimal sail settings before dark. After a tack off Ediz Hook and Port Angeles, I threw the “Man/woman/cat overboard” pole in the water and each sailor did several figure-of-eight drills as a review of the manoeuver and as a test of the boat’s maneuverability. I was happily surprised at the 53-foot long 15-foot wide boat’s maneuverability and ease of sail-handling. After that, the dinner of spring asparagus and pasta began but was interrupted by the cook getting seasick. I dived into the galley and finished what would be four servings of a wonderful dinner, unfortunately only two got to enjoy it. The crew, mostly made up of R2AK veterans and old friends, had forgotten to bring sea sickness medication. As an instructor and captain, I am not legally allowed to require crew or students to take medication so as uncomfortable as these experiences are they are valuable lessons about the dangers of seasickness and the necessity of bolstering your system until you get acclimatized to the motion. With fifty miles to go and as the wind tapered we decided to turn on the engine and motor sail. This would allow us to time our arrival to the ocean at sunrise. At this time I went down below for a three-hour nap before my 12 to 3 am shift. I came on deck and took the watch alone deciding to let the sick cook rest. At the end of my watch, my standing orders were to vary the speed to arrive at Cape Flattery at dawn. While I was off-watch, the wind increased from the South, and the engine was turned off. Unfortunately, too much sail was up, and when I came on deck at 6 am we were leaving the strait and entering the ocean in the dark. Which is what I had planned to avoid. We put in two reefs and rolled the jib in two feet and continued West into the dark ocean. We went out for an hour- and- a half until there was enough light to see the waves and turn around. At this point, we were surrounded by ships entering the strait and with less maneuverability than I like to have due to being overpowered. We then planned to head into Neah Bay 10 miles from Cape Flattery and get some rest and recuperate. At this point, everyone but myself was sick and eager to get back into sheltered waters. Just outside of the bay and out of the swell and chop we saw a gust of 41 knots on the wind gauge. At that point, we only had the double-reefed main and the engine on. Thirty minutes later we were tied up to a very inhospitable dock with broken cleats and rusty bolts protruding from the whaler boards. The bright white hull of the new sailboat was in stark contrast to the rusting hulks of the dying native fishing fleet. The only real cause for alarm was one of the crew falling after jumping to the dock as we landed in a 25-knot gust. The freeboard of this boat was about four and a half feet making those fender-step things a real necessity. Everyone’s spirits were very high as we all went to sleep for a three-hour nap. After a nap, we had an amazing omelet breakfast with dill, chives, smoked salmon, and chevre.

Type 2 fun

After discussing the experience and the concepts of apparent wind and the development of bailout plans we looked at the forecast ahead. At this point, the wind was dying but the next wave of weather was going to be hitting the San Jauns just when we would be returning, so we created a plan based on what we had learned about the boat’s sailing characteristics and the wind. Our trip back was mostly uneventful and the only challenge was maneuvering around the commercial traffic in the Victoria area. Instead of returning the way we came through Cattle Pass, we chose a more conservative route over the top of San Juan Island. After enjoying some fun sailing in the flat protected waters of the islands we anchored in Parks Bay for a three-hour nap followed by another take on the now-famous omelet. We did some talk about emergency procedures and after we discussed the route the boat and owner would take back to Anacortes they dropped me off in Friday Harbor.

Some lessons can be learned through reading and study but some lessons require getting your feet wet. Hopefully, when tackling dreams as big as this we can do the due diligence necessary to be prepared for the new scary world of big water sailing and hopefully, we can take the time to organize shakedown sails like this one where we can practice before we put ourselves and boats into situations that we can not retreat from. This was a hugely valuable experience because we learned about what the boat likes and doesn’t like, what modifications need to be made before the big trip south, and most importantly where everyone’s comfort and resilience levels are. Getting seasick sucks and I would say that in weather like we were in not taking medication is not an option. There are no passengers on a boat like this. Everyone aboard represents a liability to one degree and they need to work to counter to whatever degree they are a liability with their different respective abilities to help. Coastal cruising and blue water cruising can all be done without sailing in “bad weather” but extreme patience that we moderns are not practiced in is necessary to avoid putting the boat and crew into the rough stuff. Unfortunately, the harsh realities of work schedules and life tempt us into these inclement weather situations and we have to be prepared to deal with them.

“There are no passengers on a boat like this. Everyone aboard represents a liability to one degree and they need to work to counter to whatever degree they are a liability with their different respective abilities to help.”

Parks Bay for a nap before heading into Friday Harbor

All smiles and appetites back.