With this log, I’ve tried to review and share what I’ve learned on these adventures so I can improve my work and share what I’ve learned.

In the past, I’ve gotten in the habit of sharing my logs and personal notes in greater detail and now I think that I need to focus more on the particular lessons because I am getting behind on editing these logs that often exist in pretty cryptic short-handed form.

I think every mariner should keep a log so I’m demonstrating one way of doing it. In 2024 I hope to streamline this process more so the most important lessons are shared more quickly. I will share more about this process as it unfolds this year.

First I want to share a little about a sailor who started as a student and who I now consider an offshore shipmate and crewmember of the highest order. I met John Palmer in 2017 teaching a Cruise and Learn in the San Juans. John and his two grown boys made the class a very fun week. When I started GBA his wife reached out and asked if I would offer a gift certificate for John's birthday. He and his sons joined the crew of Journeyman GBA’s Cal 40 and training vessel at the time to do an Advanced Coastal Cruising class and the Oregon Offfshore. John joined for the delivery down to Astoria and we ended the race with a second place. After John expressed an interest in joining deliveries and hired me to help him buy a boat of his own. Six years later John owns a fine Wauquiez Centurion and has joined on many deliveries. He now has thousands of blue water miles and coastal miles under his belt on a variety of boats. John is top of my list of crew to call for deliveries. He has all the merits of a good delivery crew member. Ready and stoked to go, trusts me and my choices, has all of his own gear, has a stomach of steel, can make a meal for a big crew out of almost anything, and most importantly is a good conversationalist yet capable of long silences. John is a retired fire captain and has many great stories and there seems to be an overlap between our work and life choices, oh and we like the same music. In the delivery of this yacht, John would serve as the first mate.

It was the spring when the owners of this 2005 Leopard 40 contacted me about helping them deliver their boat to SF. They told me they hoped to learn something along the way so they could continue to Mexico without help.

To think of all the strange places I’ve had to sleep on deliveries…

Their sailing background consisted of a cruise and learn aboard a catamaran in the Caribbean with four other people. I later learned that in the week’s training cruise, they only got 15 minutes of sailing experience. Since buying the boat they had been out a few times but boat work had prevented them from getting much experience. Built in the early 2000s the catamaran had presented a number of serious mechanical failures and found its new owners more handy than they had thought they were (if not behind on getting to know their new vessel underway). I told them we were going to proceed with the planning necessary to make a trip like this with a green crew. Delivery of boats like this and offshore hands-on training are different things. One is done with a crew of vetted and experienced sailors like John Palmer and at a pace that could traumatize the fledgling would-be mariner and one is done at a slowed pace with plenty of stops and time to discuss learning opportunities as they arise. It can take a week with a strong crew to get to SF from the northwest and with more inclement weather. But even a good window of a week in calm weather the window may close or mechanical issues may present themselves and may jeopardize the chances of reaching the destination. What I have learned from doing both of these types of passages is that people looking to learn while underway, should take their plans of a destination off the table and focus on absorbing as much as they can from the experience that way they can continue safely on their own. When I speak about this to boat owners I describe these two types of passages and my role aboard as the difference between me wearing the captain’s hat and the teacher’s hat.

The captain and teacher have similar roles, but their differences are the most important. A captain gives orders to a known crew on a need-to-know basis, while a teacher gets to know their students to impart knowledge and create learning experiences. The captain and crew are more immediately capable, but this power dynamic can slow down the crew's development and progress. The teacher and students take more time but can eventually help the students become independent.

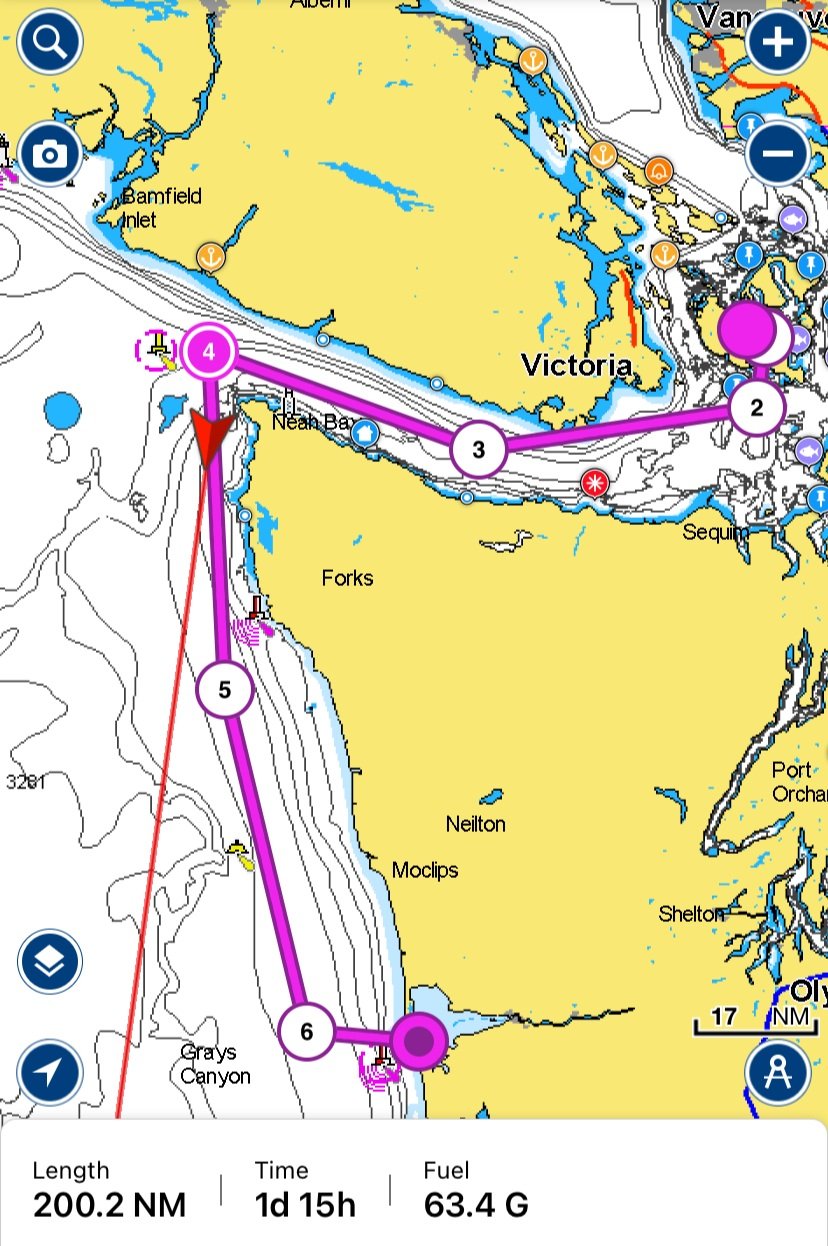

We left a day later than planned to accommodate John’s schedule after his return from another delivery helping a fellow GBA alumni he met on an Island Packet 350 delivery move his boat down the Washington Coast. This was a welcome delay as it allowed the current-opposing winds to settle in the Strait and for the owners to do some troubleshooting on one of the engines.

On the way out of the strait, we noticed the running light on the bow wasn’t working. We managed to remove it underway and clean it with a wire brush but it was going to be a temporary fix as the LED bulb was distorted from corrosion. It was hard to remove the bulb cover because there was a docking light installed above. Poor design here and a red flag for the readiness of the vessel for the trip.

Motoring out to sea in calm water on the infamous Straits of Juan De Fuca

Multihull boaters do it different

Best fueling opportunity. A calm exit of the sound is great but it costs the go juice.

The weather did settle, so much so that it required that we motor more than usual this time of year to keep up with the time allotted for the passage.

This motoring necessitated going into Westport to fuel up. This was done very quickly as the safe time to cross the Greys Harbor Bar lined up with the fuel dock hours with little time to spare. Once underway the engines ran smoothly but by the third day, diesel fuel fumes were coming up from the fuel tanks under the aft bunks because the inspection plates had been leaking from the pressure caused by the sloshing fuel. This is the sort of thing that would have been discovered if the boat had been used or “shaken down”. This required ventilating the aft cabins to make them more tolerable to get the rest necessary to crew the boat safely.

The next incident came when we tried to tack through the wind with the help of the engines. The port engine did not start and required bleeding which should be avoided in the future because the tiller of the Port rudder comes dangerously close to the spot that allows access to the lift pump and could hurt someone in that position. There was quite a bit of air in the line and it is not clear to me whether it was because that engine had a squeeze bulb installed in the line and was leaking or that the squeeze bulb was installed by the prior owner because the engine needed to be bled in the past for some other reason. There was not a bulb on the other motor’s fuel line. This installation of a squeeze bulb is unusual and not recommended. Another reason that it could have been installed is that it was used to prime the Racor water separator after replacing the filter. Either way, I advised that it be removed and all the fuel connections and hose clamps be tightened once out of harm’s way. Another thing that began to happen at this point was the autopilot kept disengaging with the moderate following sea that was beginning to run and required that the helm be watched closely to prevent the boat from rounding up. This was mostly a concern because steering by hand and by compass requires the experience only half of the crew possessed. This is not the first time I’ve experienced this with multihull sailboats. Without going into too much depth this is because catamarans often have large roached mainsails with fractional rigs (smaller headsails) and little shallow rudders. They can sail fast upwind and across the wind and navigate the shallow waters of the Caribbean but off the wind in following seas this rudder sail combination tends to make the boat want to round up. Which, if I’m honest is a little scary because, in conjunction with swept-back spreaders (another thing that goes with large roach sail plans), you can’t luff the main like you can on other boats with the wind on the beam. So you have to reef the main often either by turning around into the wind and luffing it or by pulling the main down while sailing downwind which is hard without high-end batten cars. In addition to these challenges jibing these big mains can be scary so in moderate wind I opt to tack the boat around so I can let the load come off and back on the rigging more gently. In more than moderate winds this method (often called a “chicken jibe”) is aided with the use of the engines. The downside is heading into the wind and the waves while you do it.

Cnav practice offshore

This is a new and improved specialty of Jon’s: The Seattle Dog in a tortilla. Very good and less messy that the original version. Jon has made a name for himself on past passages making food when no one else has the stomach to go bellow.

We also went from a three-hour watch to a four-hour watch system to allow for more downtime to rest but stuck with the doubled-up supervised watch system. One watch when I came up with my watchmate to relieve the crew I noticed my watchmate nodding off and after only a little while on watch, I offered to take the remaining watch myself so he could get some sleep.

“..Not long later a wave came in through the forward port hatch to drench the port bunk along with John, his bedding, and gear.”

Once we were passing Cape Blanco a wave came down the deck and the aft port cabin’s hatch was open and drenched the owner’s cabin and bedding. I didn’t know this hatch was open to introduce fresh air due to the build-up of fumes. Not long later a wave came in through the forward port hatch to drench the port bunk along with John, his bedding, and gear. This was due to old hatch seals. The waves were primarily on that side of the boat so it is not clear that the same wouldn’t have happened to the other side’s deck hatches. The seas were not big at this point and the wind was below ten knots so I was trying to imagine what would happen when things got rougher at the next cape.

I caught two of these beautiful Albacore Tuna. One by accident and one when the lure slipped back overboard and I had to jump into the engine room to bleed the fuel line when one of the engines stalled.

Look out!

Later in the passage, there was lightning on and off the coast. When we discussed making regular handwritten notes of our latitude and longitude in the event that we were struck and the GPS lost reception. I was told then that there were no paper charts on board to use to plot our position and navigate to safe harbor if we were struck and lost our electronics during what was turning out to be a foggy trip.

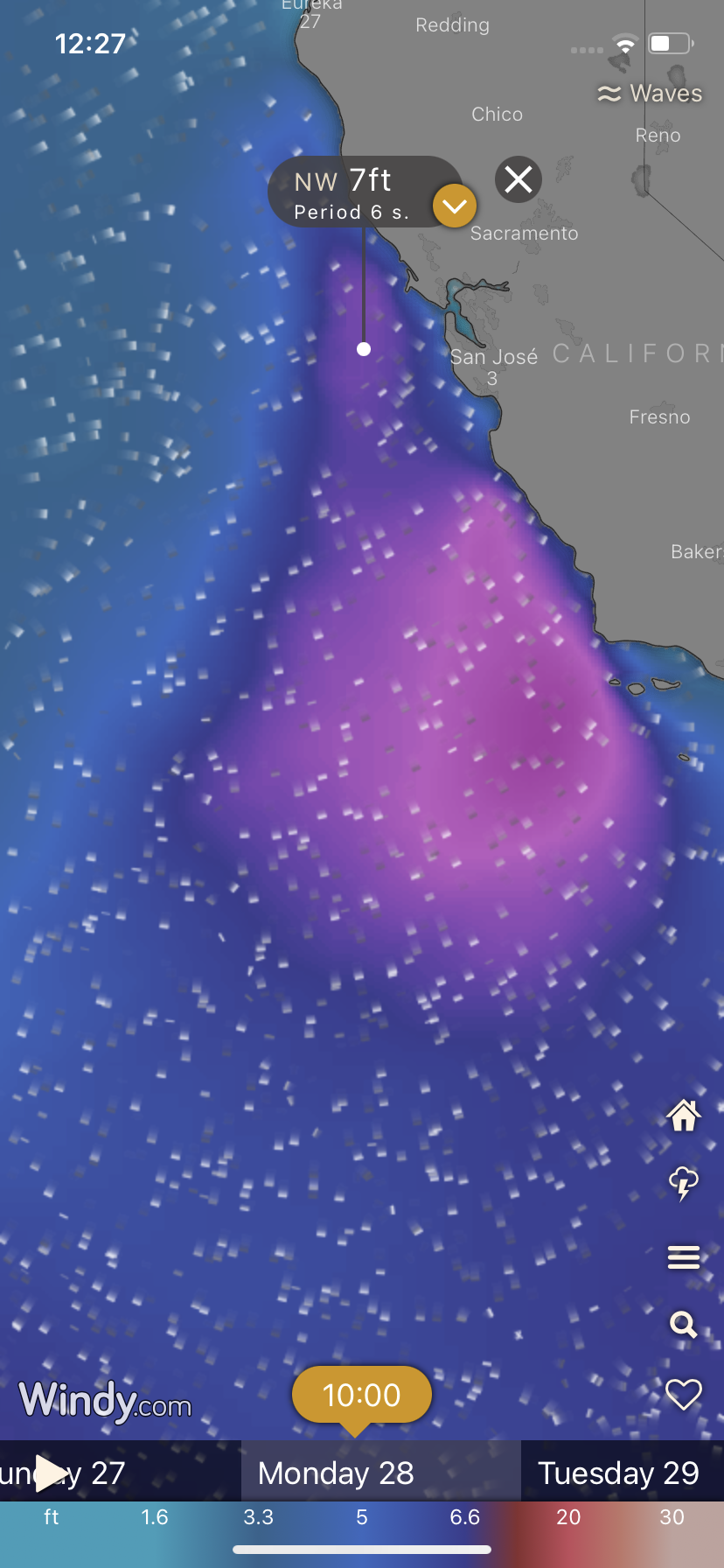

Once the bunks and gear were wet in conjunction with the other factors: crew fatigue, rigging concerns, fumes, leaks, autopilot, and fuel levels the decision was made to head in. By the time the bunks would be dry and the laundry and inspection plates done the weather window was going to be closed. 9-foot seas at 8 seconds with 30+ knots forecast would be beyond the boat and crew's ability to safely transit the dangerous coast off Cape Mendocino. The options were to wait for the weather to abate and repairs to be made and charge lay days or curtail the delivery in Eureka.

It would have taken five lay days until the next weather window opened up which would have required recrewing.

Unfortunately, I had a contracted commitment starting the 1st of September that was scheduled to last 7 to 9 days (another cat delivery to SF). I offered to come back and move the boat with them from Eureka to SF after it was completed. If this didn’t seem like a good option I offered to contact a local fisherman friend with experience on the coast to join them. They refused deciding to go on alone when the next window presented itself. After an uncomfortable time, they paid the travel expenses for John and me to get home. I suspect they were upset that we didn’t just go regardless of the weather and the boat’s condition. It's tough because when you help someone avoid a scary situation at sea, they don't realize what you are saving them from.

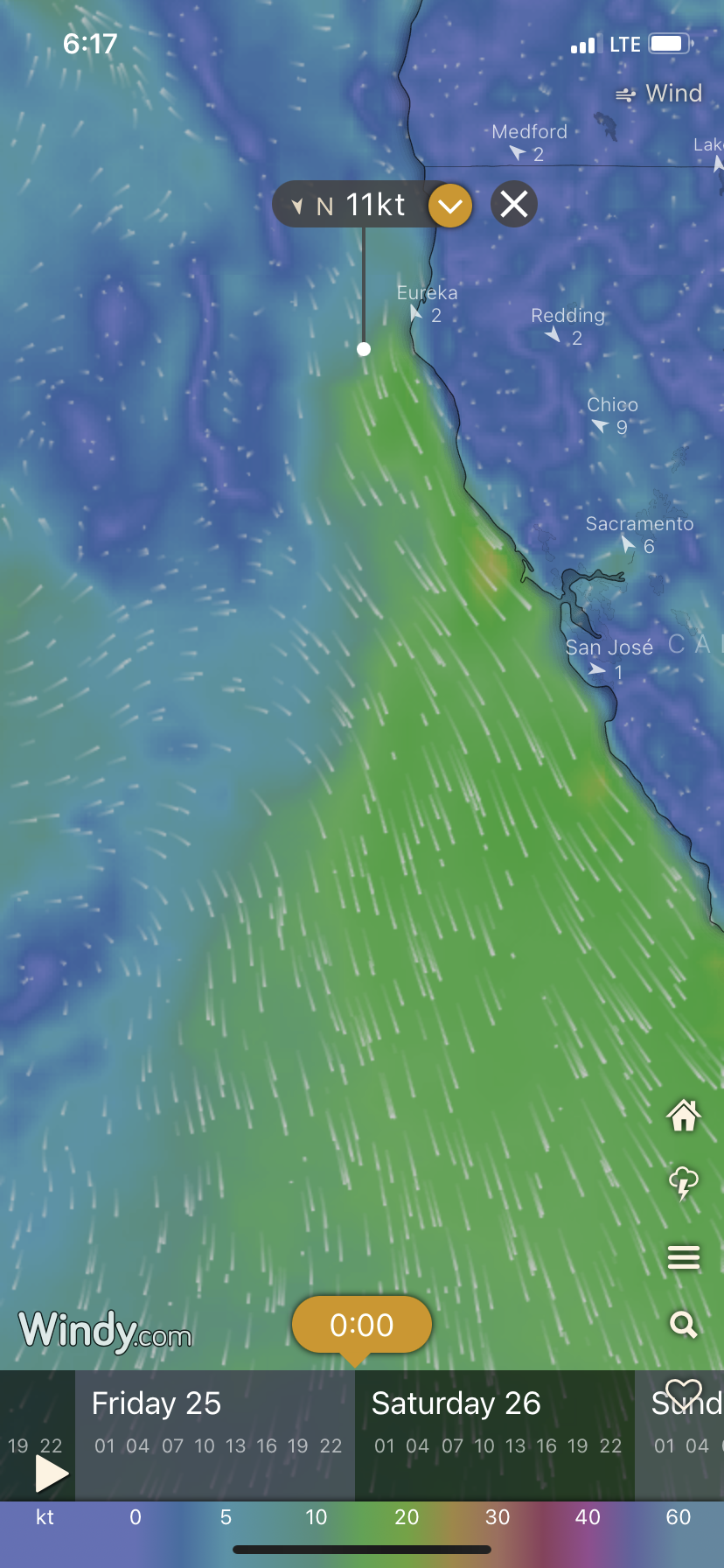

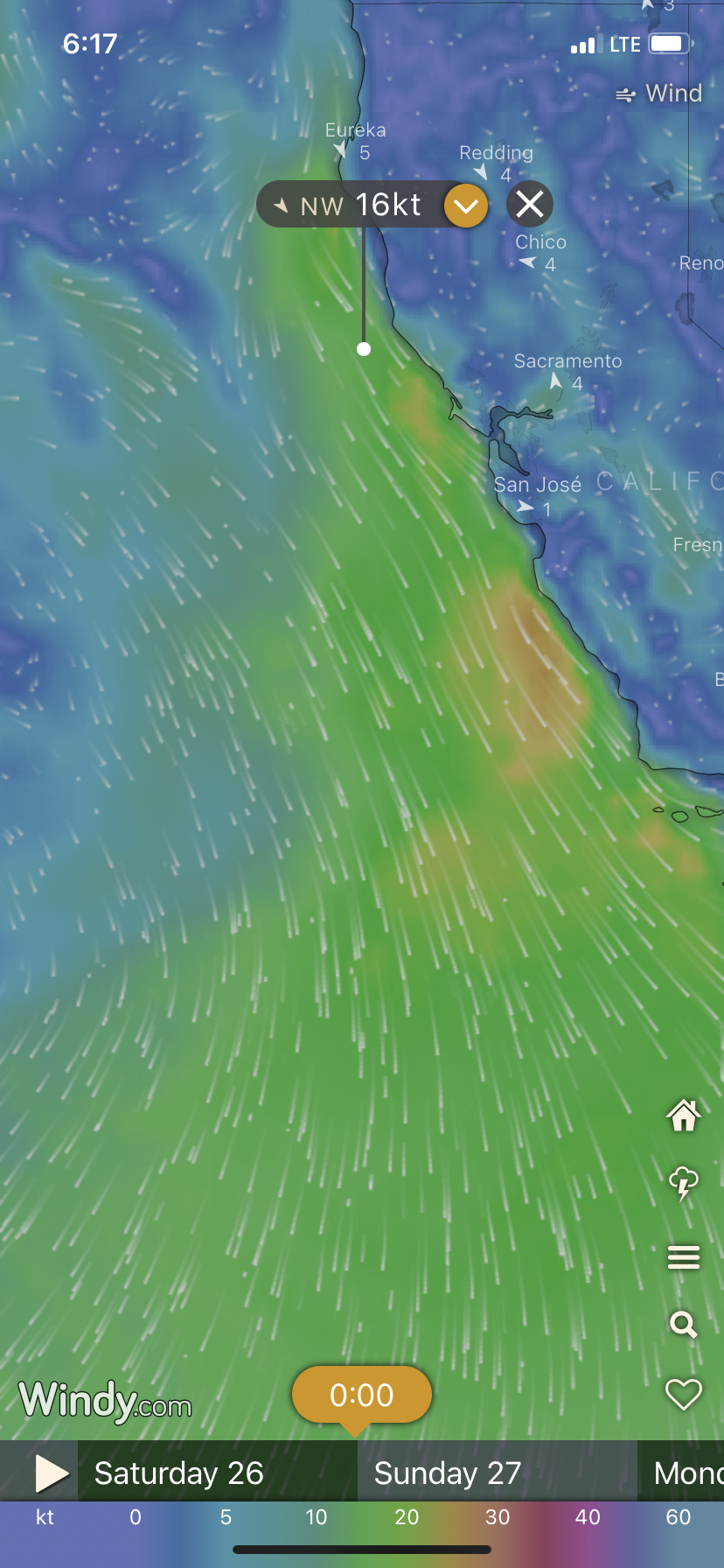

The following are screenshots of the forecast on Wednesday the 23rd for planning the cape roundings. It shows we just had enough time to get around before the 20+ knot conditions.

These are the forecasts taken on the 26th showing that sometimes a little delay can be significant.

I only received half the payment I expected for this job because of the setbacks the poor prep caused. On top of that, the time I set aside for this job clashed with a 30-day delivery on a 2018 Amel 55 that I could have taken instead.

This story shows the ugly side of things but this is a seasonal business and the reason I now expect full payment prior to the departure.

Takeaways

-Shakedown your boat prior to a trip like this. The Strait of Juan De Fuca is a great proving ground for crew and vessels alike. We offer shake-down opportunities every year on the easter straight.

-Discuss contingency plans early. These passages are about learning and moving a boat. Sometimes trying to get the boat moved gets in the way of learning. Motoring to make time gets in the way of learning how to sail. Learning how to drive the boat in moderate conditions in the daytime is the only way to prepare a sailor to do it at night.

-Don’t rush. Buying a boat, taking a crash course in sailing, and leaving the first year is not a safe way to approach the ocean. These folks would have been better off hiring an instructor to help them learn their boat rather than joining a multi-hull “cruise and learn” with 3 other couples. Cruise and learn classes cater to bareboat charter prospects. This way they could have sailed their own boat down the coast at their own safe pace.

-Spare fuel. Extra fuel helps with deliveries. If you have a window and need to go far, reduce the number of stops you need to make. This reduces risks at the bars and time wasted coordinating bar crossings with fuel dock hours.

Some hard lessons for all on this one but good conversation and food were had as well.